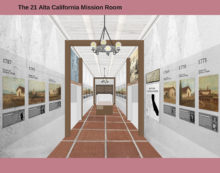

Sharing our history

21 California Missions

at the Mission San Jose Museum

The Missionary Path: Although the Spanish occupation of California did not begin until 1769 forces were at work the year after the first voyage of Columbus, which ultimately brought Spanish missionaries to the Golden State of today. In 1493 Pope Alexander VI drew an arbitrary line on the map, which was to divide the spheres of interest of Spain and Portugal, and declared that all colonizers should be accompanied by “worthy God-fearing, learned, skilled, and experienced men to instruct the inhabitants in the Catholic faith.” Controversy arose immediately. The religious element held that all men and women were brothers and sisters, and that the newly discovered territories belonged first to the King, and then to the original inhabitants. Colonists thought of the natives as sub-human beings with no right of private ownership. The King of Spain used both of the opposing forces, first one, then the other, to advance the expansion of the Spanish Empire.

Then Charles V issued a code of “New Laws” which eventually became the foundation of the California mission system. It stated that the Indians should be permitted to live in communities of their own; they should be permitted to choose their own leaders and councilors; no Indian to be held as a slave; no Indian to live outside his own village; no Spaniard to stay in an Indian village for more than three days, and then only if he were a merchant or ill; and the Indians to be instructed in the Catholic faith.

Under the protection of these new laws, religious communities begin to spring up in Mexico, and Central America. Although strenuously opposed by Spanish plantation owners, and not given any great favor by the King and his viceroys, even so the missionaries were self-supporting and provided an inexpensive means of securing frontiers against other European ambitions.

The court of King Philip II became the richest in Europe after Spanish conquest of islands of the Pacific such as the Philippines, Spanish galleon ships plying the vast Pacific, bringing treasures of the Orient, needed safe harbors on the western Mexican coast. It was Vizcaino in 1602 who first discovered Monterey Bay and first described upper California as the land of “milk and honey” – the best port that could be sheltered from all winds, much wood and water, settlements of friendly Indians; springs of good water; beautiful lakes covered with ducks and many other birds; good meadows for cattle; fertile fields for growing crops. Yet the discovery gave Spain no immediate advantage. A hundred years later, their influence extended only up the barren coast of Lower California, where the Jesuits had established a chain of missions.

The Jesuits had made their own rules and commanded their own security forces. This was not to be tolerated by secular elements. Eventually, the Jesuits were replaced in Mexico by the Franciscans, who were to extend the mission system into upper California—but under the control of and in cooperation with Spanish authorities.

Miguel Jose Serra was born on November 24, 1713, the son of a farmer at Petra, Majorca, in Spain’s Balloric Isles. He was baptized at the parish church of Saint Peter’s, and received his first education at the Franciscan Friary of San Bernardino. Both of these buildings, as well as the rough stone birth dwelling, may still be seen at Petra. On taking his religious vows in 1730 Serra took the name Junipero, after a beloved disciple of Saint Francis of Assisi. Later, the little padre, scarcely over 5 feet tall, who was to become the “Apostle of California” arrived in Mexico. There he and governor Portola planned, how to expand Spanish domain into Upper California by extending the chains of Missions northward.

Due to the uncertainties of the times, the soldier and the priest decided that their first effort, up to present San Diego, would be divided into five segments: three ships and two expeditions by land, all to leave at separate times. Padre Junipero Serra, and the governor riding on mules, were in the second land party. After many hardships crossing the virtual desert, both land parties reached San Diego to find only two of the ships in the harbor, with the crews and soldiers, who were passengers, badly decimated by scurvy. The third ship was never heard from.

Thus began he founding of the famous 21 missions of the California chain along “El Camino Real,” the Kings Highway.

This famous California roadway runs the length of the state from San Diego to Sonoma, linking the “jewels” of the mission chain. Later, the name was often translated as the “public highway” purposely ignoring the term “royal” as California became a republic, and then a state.

It was once just a foot trail. But as settlements and missions were established and the population grew, the trail became the main inland route for travelers. It was a stage line and eventually a highway, U.S. 101. With only a few detours, the present U.S. 101 is identical to the route the padres used. Its official historic marking is a mission bell the color of tarnished copper, arched over a single sign post with the words “El Camino Real.”

The 21 missions that dot the California landscape from San Diego to Sonoma are the relics of an ambitious plan in the European conquest of the New World. The program used by the Spaniards to colonize California was unique among the methods tried in North America. The Spanish monarchy charged the Franciscan Order of the Catholic Church, in tandem with the Spanish military, to secure the western shores of what was called New Spain, establishing missions to convert the native Indian population to Christianity. Each mission would be the beginning of a civilian town, and they would be located at regular intervals upon the entire stretch of the colony. The missions’ brief history is one of remarkable achievement and swift decline.

The missions were the primary centers of religious, cultural and agricultural activity. Spanish soldiers in nearby presidios were available for protection. For both the missionaries and the Indians, adaptability to new ways, was essential to survival.