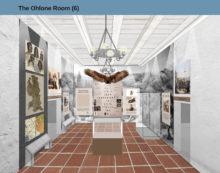

Sharing our history

The Ohlone Indians

at the Mission San Jose Museum

The Indian Way The Ohlone Indians, being all hunters and gatherers, and dependent upon what nature provided, obviously had to adapt their way of life to what nature provided. So, they built and developed a way of life which was a close fit to the particular resources of the small and individual tribal territories.

Before the Spanish set foot in the San Francisco East Bay to choose the future site for Mission San Jose, numerous tribes descended from Penutian speaking migrants had settled the land for thousands of years. The landscape of the San Francisco Bay Region was comprised of tiny tribal territories, approximately eight to twelve miles in diameter and populated with about 200 to 400 individuals. The tribelets, were associations of families that worked in unison to harvest the numerous plant and animal resources that occupied a fixed territory. These triblets have been called “independent, landholding religious congregations.” All of California was populated with these tiny tribes due to the abundant resources that were available throughout the state.

It has been determined from the Mission San Jose Baptismal Register begun in 1797 that the Fremont Plain, in the southwest corner of Alameda County, had been occupied by the Alson and Tuibun tribelets. These groups lived in numerous semi-sedentary villages year round. The boundaries of their territory are unclear, although that it may be inferred that the Alson controlled the area from the bay shoreline to an unknown ridge-line boundary in the East Bay Hills and that it extended from Scott Creek, on the modern Alameda County line, northward to an area south of Alameda Creek that may have been defined by the historic Sanjon de los Alisos drainage, where presently the Jarvis Avenue route is located. The Tuibun seem to have been located at the mouth of Alameda Creek and in the Coyote Hills area on the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay.

The beauty of the Ohlone culture comes from how much they were able to yield from the natural environment that immediately surrounded them. The Ohlone diet was extremely diverse and there was never any record of starvation, nor any mention of it in their oral tradition. They had never known hunger until the Spanish came, labeled their practices as “savage,” and imposed their own system of domesticated animals that ravaged the natural ecosystem and forced tribes to depend on mission livestock for food. Malcolm Margolin describes the Ohlones as a hunting and gathering society:

“One harvest followed another in a great yearly cycle. There were trips to the seashore for shellfish, to the rivers for salmon, to the marshes for ducks and geese, to the oak groves for acorns, to the hills and meadows for seeds, roots, and greens, to quarries for minerals and stones, and other trips for milkweed fiber, hemp, basket materials, tobacco, and medicine. The series of ripening and harvesting divided the year into different periods, and it gave Ohlone life its characteristic rhythm.”

The primary focus of the California Missions were the Indians. When the Franciscans selected the Ohlone village of Oroysom as the site of Mission San Jose, they chose an area occupied by the Alson and Tuibun tribelets who spoke a dialect of the Ohlonean language called Chochenyo. The villagers were dependent on complex interrelationships with other tribelets in the Bay Area that helped ensure their survival.

Central to the efforts of the Franciscan Padres at all of the California Missions was to gather the native peoples into villages surrounding the location of a Mission establishment. At these transitional villages, the native peoples underwent a process called reduccìón. There they were reduced into the Missions by being taught Christian doctrine and morality, as well as European cultural values. Spanish laws and government were further established by the creation of townships (pueblos) of Hispanicized farmers and artisans out of the indigenous population. Spanish law provided that Indian tribes entering the mission system would have their lands preserved intact under the management of the mission padres. The intention was to have self-governing pueblos in place within 10 years of the foundation of a given mission.

The Spanish philosophy of colonization has been termed Hispanization “the assimilation of a conquered people into Spanish society by absorption of their own culture.” The Spaniard firmly believed that the greatest gift that he could give the Indian was to remake him in a Spanish mold, which included, of course, the Catholic religion. Since Church and State were united, the missionaries were expected to be the principal agents of colonization, and as loyal Spaniards they willingly served as such, although motivated by the higher aim of winning souls for Christ. The Indians of a locality were gathered into a mission to be taught Christianity and the rudiments of European civilization. A mission was much more than a church, though the sacred place of worship was surely the heart of the mission. In addition there were quarters for the padres, soldiers and guests, homes for the Indians, workshops, storehouses, and acres and acres of land devoted to agriculture and livestock.

The ultimate purpose of the Spanish Church and the Spanish government was to embody the converted Indians into Spanish society as “useful vassals of the Crown.” But, if the Church and the government were to attain their purpose, then the converted Indians had to undergo at least three fundamental changes in their social life. First, they had to abandon their custom of avenging injury with death and accept Spanish laws. Secondly, they had to change their marriage customs. They cohabited, pairing off with various partners in succession, trying each other out, and finally arriving at a marital decision to which they would normally adhere more or less permanently unless or until a more attractive or advantageous partner entered their lives; whereupon a divorce and remarriage would take place, which meant that the new partners would simply begin to live with one another in a more acceptable pattern of housekeeping. It is quite clear from the above that the “Mission Indians” did not easily adjust to life in the Spanish world.